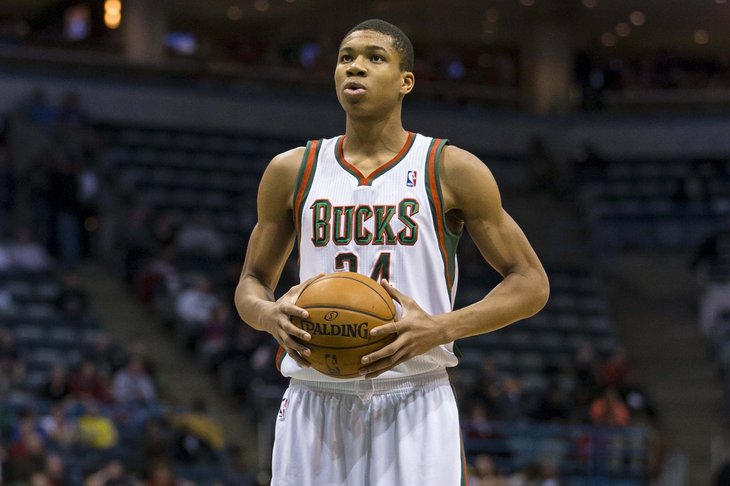

The Transformation of NBA All-Star Giannis Antetokounmpo: From a Skinny, Hungry Child to Basketball Great

Giannis Antetokounmpo of the Milwaukee Bucks reacted during an NBA game against the Indiana Pacers in Indianapolis on February 11, 2017. He has come a long way from being a scrawny, hungry boy playing with a ball in an open field in Sepolia, Athens, to starting in the NBA All-Star Game.

Born to Nigerian migrants, he was a thin, malnourished child trying to make ends meet in the modest Athens neighborhood of Sepolia. The NBA All-Star lived in constant fear of police and deportation, as recounted by his club coach, who witnessed 13-year-old Giannis and his brother kicking a soccer ball around a local field.

At that time, Antetokounmpo was primarily focused on soccer and had only just dipped his toes into basketball.

Spiros Velliniatis recalled, “He couldn’t dribble or make a layup.” However, he was intrigued by the boy’s determination and grit. “He was a champion before he became a basketball player,” Velliniatis noted.

Now known to fans as the “Greek Freak,” Antetokounmpo credits Velliniatis for introducing him to basketball. “He opened the door for us to explore basketball because my brothers and I were more focused on soccer, following in our father’s footsteps,” Antetokounmpo said.

At 6-foot-11 and 22 years old, the Milwaukee Bucks forward is renowned for his ability to soar above the rim, even as many still struggle to pronounce his name. However, persuading him and his older brother Thanasis to attend basketball practices was no easy task.

“I asked about his parents and said I would help them find jobs if he joined my club. He agreed,” Velliniatis recalled.

Despite their talent, getting the Antetokounmpo brothers to practice with the Filathlitikos club, located in a different neighborhood, proved challenging. Coach Panagiotis Zivas recalls, “We knew we had to find a way to keep the kids on the court; their success would be ours too. They were young and didn’t fully grasp the importance of consistent commitment.”

While neighbors offered some assistance, the family had little support.

Giannis Tzikas, a local café owner, often prepared meals for Giannis and his siblings to ensure they wouldn’t go hungry before practice. “Some people questioned why I was feeding the Black kids,” Tzikas recalled, noting that such comments only strengthened his resolve to help.

Antetokounmpo expressed gratitude, saying, “He helped us a lot. I saw him every day. He was a tremendous supporter of my younger brothers and the national team.”

Tzikas also remembered instances when the Antetokounmpo boys were barred from playing on local courts, noting their father often took them to ensure their safety.

Zivas added that the general manager of Filathlitikos not only assisted the boys’ parents in finding jobs but also provided financial support to demonstrate the club’s commitment. Eventually, the family moved to a better neighborhood closer to the club.

Once settled, Giannis thrived. “He quickly became a leader on the youth team and advanced to the senior level,” Zivas said. “He collaborated well with others, focusing more on blocking and retrieving the ball than on scoring.”

After a standout game where he scored 50 points with the junior team, several senior teams expressed interest in Giannis. Officials from Filathlitikos ensured that footage of the game reached a global audience, attracting attention from the NBA as well. Notably, Danny Ainge, the president of the Boston Celtics and a former star player, traveled to Greece to see Giannis in action.

“I remember that game. It took place in Volos, and Ainge sat at the end of our bench. Fans from the opposing team mistook him for a Filathlitikos staff member and began hurling insults,” Zivas recalled. “They might have even thrown objects.”

It was uncommon, yet not unprecedented, for teams to show interest in a player not competing in the top league of their country. This was reminiscent of future Hall of Famer Dirk Nowitzki’s journey, who moved to the U.S. after playing in Germany’s second division.

Zaragoza, a club in Spain, was the first to extend an offer to Antetokounmpo. Tzikas remembers Giannis’s excitement about the opportunity.

“He told me, ‘Mr. Tzikas, I signed a contract with Zaragoza for 400,000 euros a year. I’m going to buy a car and bring my family with me!’”

In 2013, the Milwaukee Bucks selected Antetokounmpo in the first round of the draft, with his contract including an NBA “escape clause,” preventing him from playing for Zaragoza. That year, he moved to Milwaukee, and his family joined him soon after.

Thanasis, his brother, is a 6-7 small forward who previously played for the Knicks and in the NBA’s D-League. Currently, he competes in Spain’s Liga but still aspires to return to the NBA. Their coach at Filathlitikos encouraged them, suggesting that their younger brothers, Constantinos and Alex, could also make it to the NBA.

Though the brothers have traveled the world for basketball, they remain well-known in Greece. Giannis once feared deportation, but now he holds his citizenship papers and is a vital member of the Greek national team.

Kostas Papanikolaou, a fellow player on the national team, remarked, “What Giannis has accomplished at such a young age is truly remarkable. He serves as an inspiration to every kid.”

During the off-season, Zivas frequently sees Giannis.

“Every summer, he returns here to train and lift weights,” his former coach noted.

In May 2016, they traveled to Athens for a game featuring Greek players and veterans. Kristaps Porzingis, a rising star in the NBA, also participated. A small crowd of enthusiastic fans packed the gym next to one of Athens’ largest public high schools to witness the game, which ended in a thrilling 123-123 tie.